In the Democratic Republic of Congo, girls lacking in educational opportunities are at risk of early marriage and pregnancy, which is reinforcing cycles of poverty and hindering the country’s development. The International Rescue Committee is mounting a systematic effort to ensure girls are enrolled and succeeding in Congo’s classrooms, so they can take control of their futures through education, and contribute toward the development of their communities.

Growing up in rural Bandundu Province in western Democratic Republic of Congo, Belbiche had lost both of her parents to malaria by the time she was eight years old.

“I dropped out of school and started working in the fields,” she says. “When I saved money from selling my produce, the boys would be sent to school."

Belbiche’s story is common across the country. When parents can afford school fees, they favour sending their boys to school over girls. The financial gains their parents might get in the short term – by saving money on school fees or by receiving a dowry through marrying off their girls – are lost in the long term. Girls who marry early, become pregnant at a young age, and struggle to raise their own families in areas where there is limited access to health care and education – and the cycle of poverty is often reinforced.

Investing in girls is proven to be one of the most potent ways to fight poverty. Thanks to a new scholarship programme* led by the International Rescue Committee and funded by UK aid, Belbiche is now back in school. But 3.8 million girls between the ages of five and 17 in Congo do not have her opportunity.

“Girls want to be useful in society,” Belbiche says, “not stuck at home living in these conditions, like my friends. I hope to become a teacher so I can give other girls this opportunity.”

Belbiche’s classmate, Elise, also lost her parents before she turned 10. She is now the primary care giver in her family. She wakes up at 5am to do housework and prepare food for her 3 siblings whom she leaves with her neighbours during the day so she can go to school.

Elise is also a student in the Vas-Y-Fille project. She has to walk two hours to get to school in the morning but is grateful for the opportunity which is denied to so many of her peers.

Despite crucial reforms by the ministry of education, which includes doubling the percentage of the national budget devoted to education (from 6.5 percent to 13.8 percent), change is coming slowly to Congo. In principle, primary education is free, but in practice underfunded schools request fees from students to cover the cost of equipment and staff, many of whom are not paid on time, if at all.

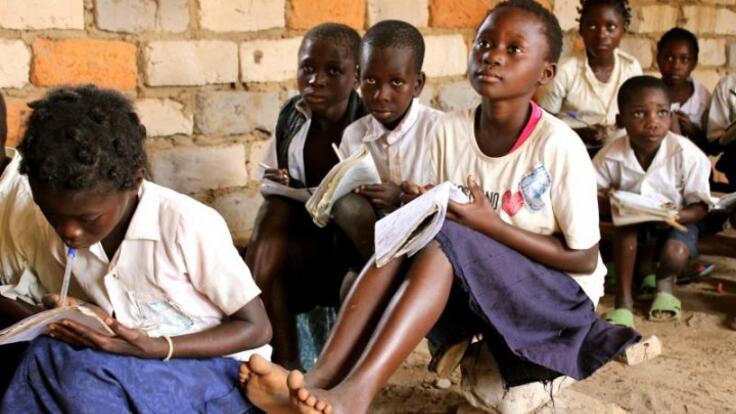

According to a recent baseline evaluation by the IRC, conducted in partnership with University of Massachusetts–Amherst, many parents cannot afford school fees for girls. Girls who do manage to attend school are handicapped by poor-quality teaching and a lack of resources—they are often the last to receive pens and books. As a result, 50 percent of young and adolescent girls scored zero on four of five early-grade reading-assessment tests.

One of the main reasons for low educational attainment and high dropout rates among girls in Congo is because their needs are not met in the classroom. Most rural schools are not equipped with basic learning materials, toilets, or adequate shelter and protection for both boys and girls. Vulnerable girls in these schools are the most at risk, and most likely to drop out.

“When I started working here a few years ago, parents would only send their boys to school,” explains Arlette, an IRC community mobiliser working in Kapalo in Katanga Province in southeastern Congo. “Girls would be married off early, sometimes as young as 11 or 12 years old, and start having many children, who are seen locally as a sign of wealth. But the cycle of poverty would continue.”

Arlette maintains that change is possible. “Parents understand the eventual economic return and benefit of sending girls to school,” she says. “They just need to be supported so they can send their girls to school.”

“This is not just a cultural problem,” adds Rose, a mother of six who is working with Arlette to create a village savings and loan association to fund girls’ education in their community. “I want my daughter to have the opportunity that I didn’t have, to learn and to create the future she wants, but we lack the financial means.”

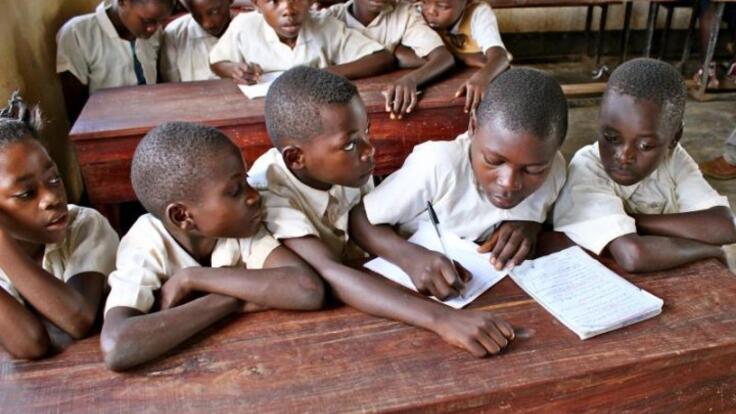

Ensuring girls are enrolled and stay in school is only the first step. Quality teaching is essential to make sure girls complete school and succeed afterward.

Sylvie Lumwe, a teacher in Katanga, recently received training as part of an IRC project funded by the U.S Agency for International Development (USAID). “Thanks to my training, I’m more aware of the barriers set against girls,” says Sylvie. “I now actively encourage and support girls to excel in the classroom, and work to convince parents that keeping their girls in school is a good economic investment.” She knows firsthand how hard it is to stay in school: when she finished her university degree, she returned home to help young girls to do the same.

Girls continue to face enormous challenges in Congo, with safety concerns, cultural bias and poverty working in consort to prevent parents from sending girls to school. But all of these barriers are surmountable. By extending access to free education, sufficiently allocating resources to rural school so teachers are paid, and training more teachers – especially female teachers – girls have a greater chance. Those who do are better prepared to end the cycles of illiteracy and poverty blighting their communities.

*Funded by UK aid, the IRC is leading the VAS-Y Fille! project, with partners Save the Children and Catholic Relief Services to improve access to education for more than 137,000 girls in five provinces of DRC where girls’ enrollment, learning and completion are the lowest.

The IRC and girls

Working in more than 40 countries and 22 U.S. cities, the IRC helps girls acquire knowledge, skills and confidence. We know that when crisis strikes, women and girls are the first to be harmed, the first to be marginalized, the first to be forgotten. They are also the first to take their families to safety, the first to unite, the first to rebuild.

Learn more about our work around the world and our involvement in this important movement to empower girls as agents of change.