Since the beginning of 2014, Boko Haram militants have abducted at least 2,000 women and children throughout Nigeria and coerced numerous children to join their ranks. The ongoing violence has forced some 1.6 million people from their homes, among them 800,000 children.

Nina Weisenhorn, an education expert with the International Rescue Committee, recently spoke with several young Nigerians who fled with little more than the clothes on their backs. She reflects on their courage and their determination to get the education they deserve, in spite of the hurdles they face.

I had the opportunity over the past month to meet with young people from the displacement camps where the IRC works in Yola, in eastern Nigeria. My colleagues and I talked with them about their lives in the crowded camps, where a staggering 400,000 people have found shelter from Boko Haram violence. When we asked what type of support they needed, one 17-year-old girl replied, “The most important thing for young people is to go to school.”

Food is another priority, she told us, adding that there was yet another urgent need. “The community needs safety,” she said.

I was struck by the pervasive fear of violence common among these innocent children. Their parents similarly reflected on how children were becoming increasingly worried and sad. Girls, in particular, were described as withdrawn and antisocial. One parent noted how desperate the situation has become: many girls are engaging in sexual activity in return for money, food or clothing. They have no one to protect them. Boys were described as aggressive and engaging in criminal activities. Without school, children are without a comforting, supportive routine that can help alleviate the stress and uncertainty of not knowing when they might have to flee again.

“Young people just sit from morning ‘til night without anything to do,” said one parent. “I fear for the future of the children.”

Even before security deteriorated here, I knew that Nigeria had more children out of school than any other country. For many girls, the chances of ever seeing a classroom are bleak—only 12 percent of ethnic Hausa girls from the north attend primary school. “My parents do not want to send us to school outside of the camp,” a 10-year-old girl in Yola told us. “It is too far and the road is dangerous. They do not have time to take us there.”

Despite these challenges, the young people and parents we spoke with are determined to transcend their situation, an attitude that reaffirms for me how important it is that children can learn in schools that are safe and protective. The role that the IRC plays in creating a trusting and caring environment for children is essential if they are to regain control over their surroundings and cultivate hope for their future.

Our team of education and child protection specialists are working with school staff and local organisations such as religious and women’s groups to map out the most dangerous areas children cross through when they travel to school and to create school evacuation plans. Whether it be suggesting different routes for children to take or having a watch guard at certain cross points, this community effort will help ensure children feel safe on their journey to and from school as well as in the classroom and schoolyard. Children will trust their teachers to protect them from threats of violence from other students and outsiders, and know that teachers will never exploit or abuse them.

With this end in mind, I have been working with my colleagues here to engage the whole community in creating a safe learning environment. Understanding that everything is connected, we have been working alongside community and religious leaders and parents to monitor tensions and violence in the community, potential threats by armed groups and individuals, and changes in children’s behaviour. As our education programme scales up, the team will continue to work with the community to develop relevant and practical solutions for keeping children safe.

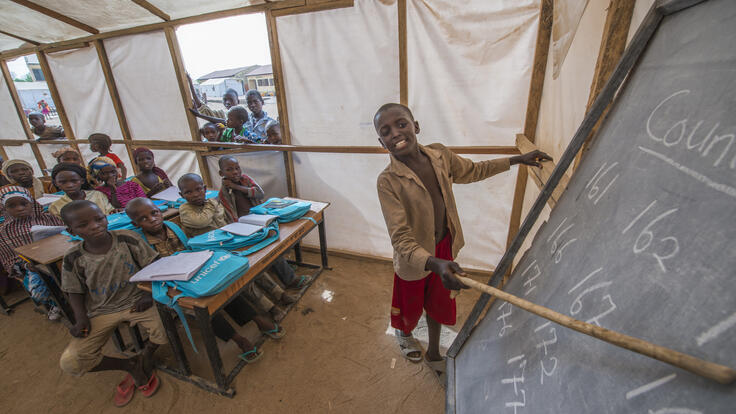

While my mission here is coming to an end, our team, with support from the U.S. Agency for International Development, will continue setting up nearly 100 formal and informal education classes for displaced children in northeast Nigeria so that their dreams of returning to school can be realised.

The IRC will continue to train teachers in reading, writing, maths, and social and emotional skills as well as organise structured play for children. We will also help administrators to establish school policies and procedures that keep children safe. And we will continue to work with community members and parents to ensure children will have safe learning environments.

Having a safe space where they can learn and play — and simply be children — is enormously important for young lives turned upside-down by conflict. As one young girl told me, “School and recreational activities help us forget what happened and allow us to make new friendships so we can deal with our situation.”

Read more about our work in Nigeria here.