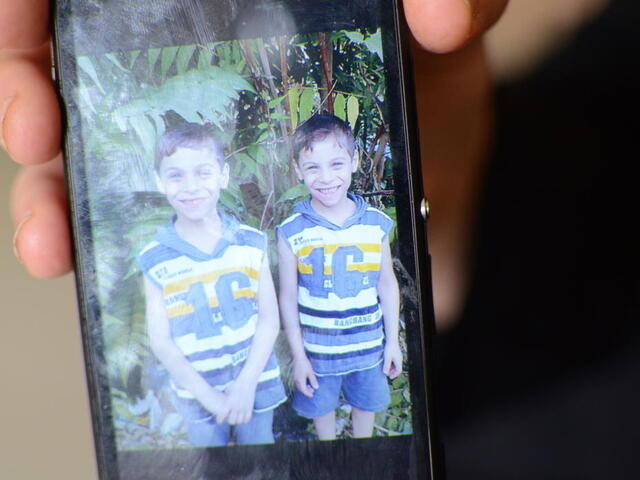

Nothing scares 13-year-old twin brothers Yusef and Hamza more than not going to school. It’s their only fear in life. Even in Syria, when bombs dropped around them, the brothers bravely made the dangerous five-minute walk to school every day because, for them, education meant survival.

“Our mum said, if we die, then we die, but we have to keep going to school because there’s a chance we may live,” recalls Hamza.

“We weren’t afraid because school was a safe place for us,” Yusef adds. “We loved to go.”

What gave them courage? “Our future,” Yusef exclaims. “We know that a good education helps you become something in the future.”

A half-million children at risk

Yusef and Hamza grew up in Damascus and loved going to school, even when war broke out seven years ago. The brothers’ mother, Bashira, would escort them on their brief daily journeys, well aware of the risk but determined to see her sons educated.

“Education is fundamental,” she explains. “We knew the war was not something that would last for one or two months, so I couldn’t take them out. The risk is also great not to go to school.”

Three years ago, the family left Damascus to visit relatives in the village of Qaroun in the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon. They fully intended to return to Syria, until they learned that bombs had hit their house and the children’s school.

Yusef and Hamza are just two of the nearly 500,000 school-aged Syrian children living in Lebanon, a quarter of whom have no opportunity to study. Local schools have reached a breaking point—they lack resources and physical space, even with the government mandating “second shifts” at public schools so Syrian children may attend classes.

As soon as they could, the brothers enrolled in the second-shift classes. For a brief time, they worked in the evening distributing coal to help provide for their family.

“They told me that they would work and save money so they can replicate the house we lived in—the furniture, the carpets, everything,” Bashira says. “But I didn’t want them to work. They came home very late and it’s hard work for children.”

Once top students in Damascus, the brothers struggled in Lebanon. Yusef found it difficult to understand Arabic grammar while Hamza grappled with English, a language he hadn’t studied in Syria. They also had trouble making new friends.

“I felt like a stranger,” Yusef admits, “like I didn’t belong because I am Syrian.”

“Hold on to dreams”

But the boys refused to give up. They enrolled in support classes offered by the International Rescue Committee (IRC) to Syrian children struggling in Lebanon’s public schools. The program builds core competencies in math, Arabic and a second language (English or French), with structured tutoring and learning activities. To date, the IRC has reached more than 4,300 Syrian refugee children across the Bekaa and Akkar governorates.

The boys’ IRC teacher, Iman Al-Hajj Hasan, found them discouraged and timid at first, but describes them as extremely intelligent and eager to learn.

“They just needed that extra push and encouragement,” she says. “It’s important to create an encouraging environment, especially for children who survived a war.”

Iman noticed Yusef and Hamza’s passion for literature, particularly poetry and short stories. To help them improve their language skills, she encouraged them to write—at home as well as in the classroom.

The brothers’ test scores improved. They developed a new sense of confidence and began to interact with other students. They even shared their writings with their new friends at the public school.

“I write from my imagination,” says Yusef, who has several notebooks filled with his literary creations. He has written six stories and hopes to publish them one day. His favorite: an interpretation of Aladdin.

The brothers dream of becoming professors; they see themselves as helping to educate the next generation. When asked what advice they have for children unable to attend to school, Hamza stresses the need to hold on to dreams.

“I’d say not to lose hope,” he says. “Study on your own if you have to—just don’t lose hope.”

*Last names omitted for privacy reasons.