Thousands of children in war-torn Aleppo are trapped without food, water or medical care as the city collapses from many months of intense aerial bombing.

The carnage took the lives of 16-year-old Hiba’s* parents and sister, but against all odds she was able to escape to Jordan with her three younger brothers.

The war in Syria spares no one. Many children have lost their families – left to embark on a journey to safety alone without any protection. Hiba and her siblings waited three months at the International Rescue Committee centre for unaccompanied minors in Azraq while aid workers took the steps necessary to reunite them with relatives already in Jordan.

Hiba shared her heartrending story with us:

In 2011, the war in Syria started. We left our neighbourhood in Aleppo for another we thought was safe. But a missile hit the bakery where my dad worked and he died. We spent two years mourning; there wasn’t much joy left in our lives.

But my mother made us feel like life could be normal again, and that there’s hope in this world. She took us to another area, which was safer. We stayed there for two years. We could come and go whenever we wanted. There was a strong sense of community; people were united. You would feel as comfortable out on the streets as in your own home. I used to go to school also; I studied until 10th grade.

I have fond memories of my father; I consider our time together to be the best days of my life. I remember one time—it was during the month of Ramadan—after Iftar [breaking the fast meal]—my dad decided to take us on a trip. He took us to the amusement park and we had such a good time.

On the way home, he opened the car’s rooftop and my sister and I stuck our heads out of the window. We stayed up until 4am! Imagine, it was that safe that we could stay up so late and nobody would bother us.

The bombing

It was Feb. 21. My younger sister, Ghazal, was playing with her friend out on the street, just in front of my aunt’s shop. I was in our house alone. My mother was having coffee at our neighbour’s house and my brothers were out playing with their friends.

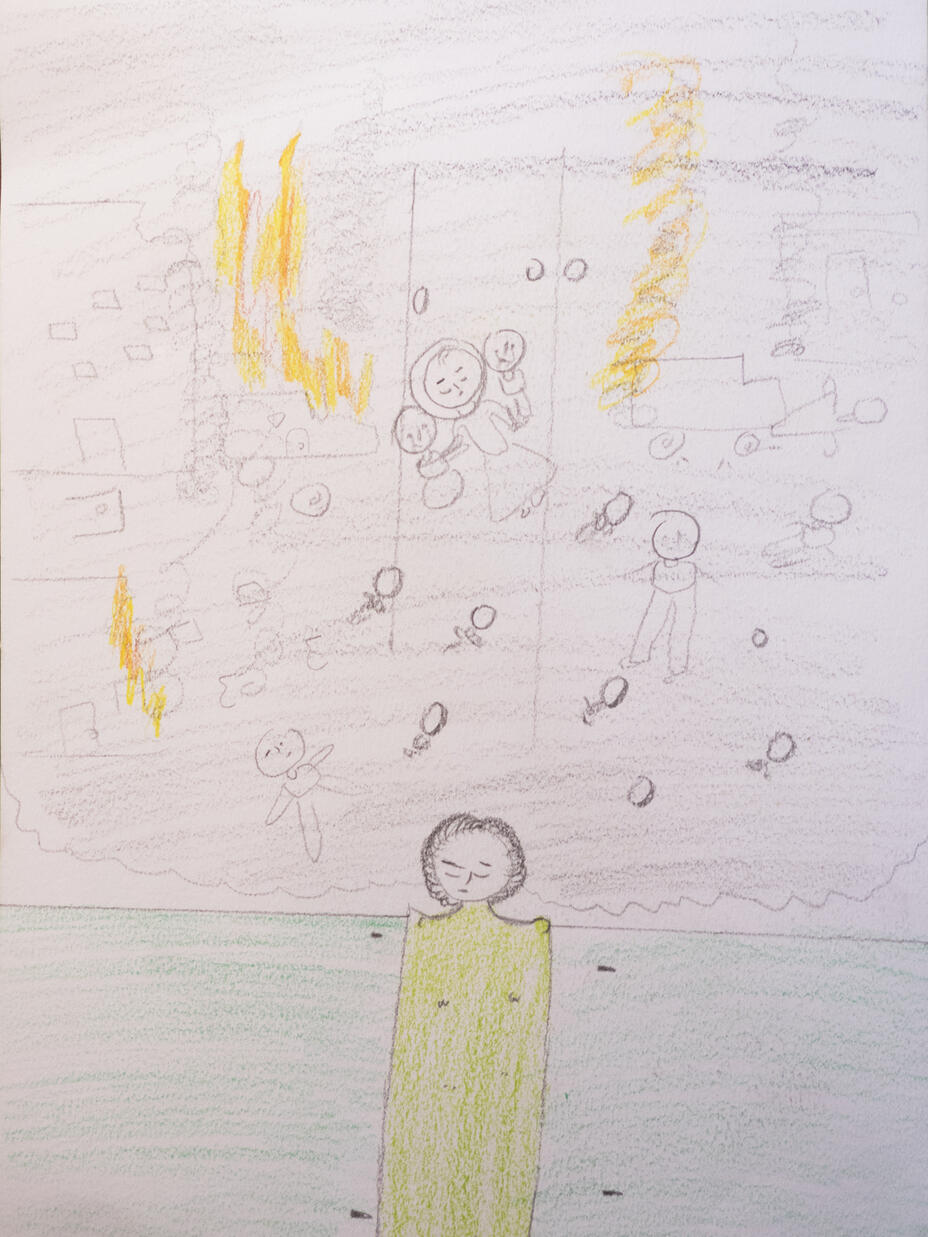

When the bombing happened, I passed out because a door fell on me. A man pulled me out, and when I woke up, everything had changed. My home was destroyed.

I went running to look for my mother, and I found her and my two brothers. My mother started screaming and went looking for my sister. I was told to stay behind.

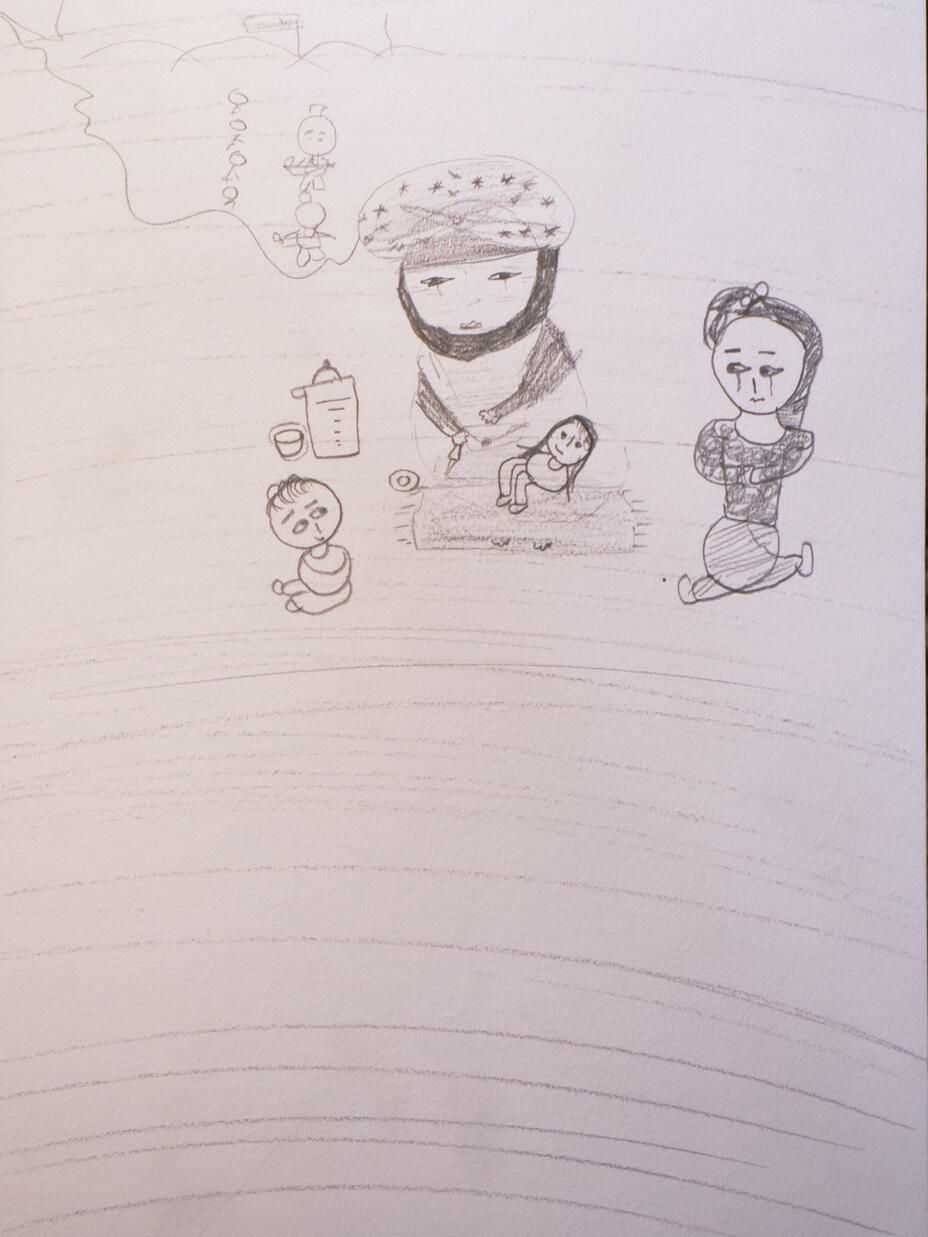

A second bombing killed my mother, along with my sister, who was only in first grade. At 12am, we found my third brother alive.

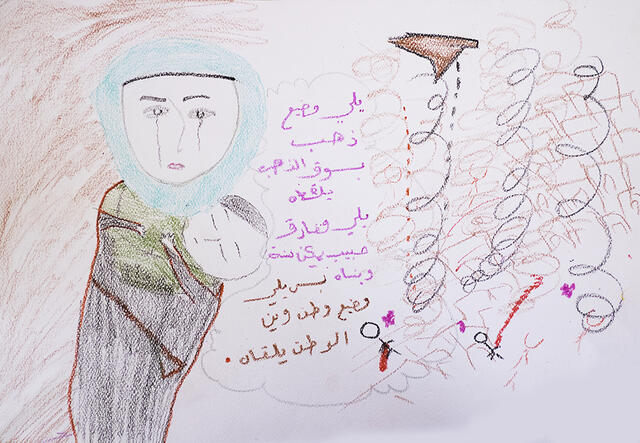

My mother was a strong woman. She would provide for us. She mourned my father’s death for three years, but people told her that it’s a long time to mourn. So she stopped wearing black and started wearing brighter clothes. But then she was killed.

The journey

When my mother and sister died, my brothers and I stayed at my uncle’s house for a month. After that, my grandparents asked us to stay with them in Amman.

I couldn’t bear to stay in Syria. It kept reminding me of what I lost—it drove me crazy. My brothers and I chose to leave Syria all together.

We made the journey to Jordan alone. My aunt helped us get a taxi, which dropped us off close to the border. We walked to the berm [a no-man’s land between Syrian and Jordan].

During our journey, we were supporting each other. My oldest brother, Mousa, 15, and I took care of our younger brothers Ahmad, 14, and Abdo, 12. My brothers are all short-tempered ever since our days in Syria; they can’t handle too much pressure.

They’re not easy to deal with, but they’re my brothers and I have to take care of them. I usually try to advise them and give them direction on what’s right and what’s wrong. If they don’t listen, I don’t push them.

#ChooseHumanity

Join our call to make world leaders accountable for real change for refugees.

Add your voice

I only brought pictures and a piece of clothing that belonged to my mother, which still carries her scent. I also brought my little sister’s pajamas that she was wearing before she changed and went to play the day she died.

It’s not a nice place—the berm. It’s a vast desert with so much sand and many tents. It looked like half of Syria was there. Once we arrived, I went to the guards and told them we’re alone. They looked at our papers, then at us, and immediately let us cross [the border into Jordan].

There was an officer there who was very kind to us; I will never forget his kindness. He gave my brothers and I clothes, food and money, and found us a place to stay with very nice people.

He told us that we will be going to a better place tomorrow, and it was true. We met people from the IRC and then went to the child-protection reception area—the nicest place ever.

The trauma

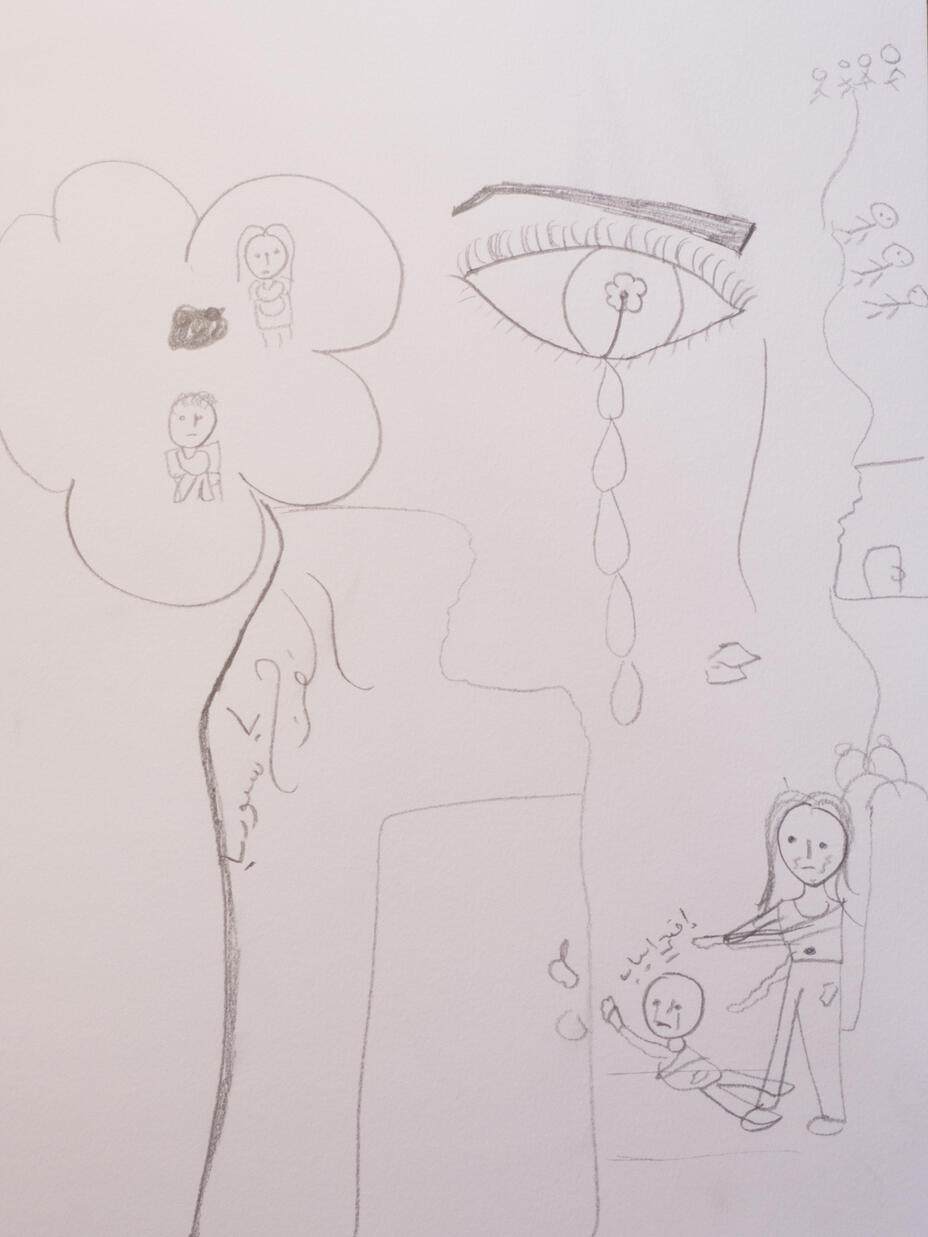

I used to sit next to my mother’s grave and found comfort in that. I cried throughout the whole journey to Jordan. I would think back and regret ever fighting with my sister. If I knew she was going to die, I would have never fought with her.

When we got to the child-protection reception area, I was surprised that I was still standing on my own two feet. I thought I would never be able to get over of my grief. But I found that the IRC staff, and the other girls there, are nice people.

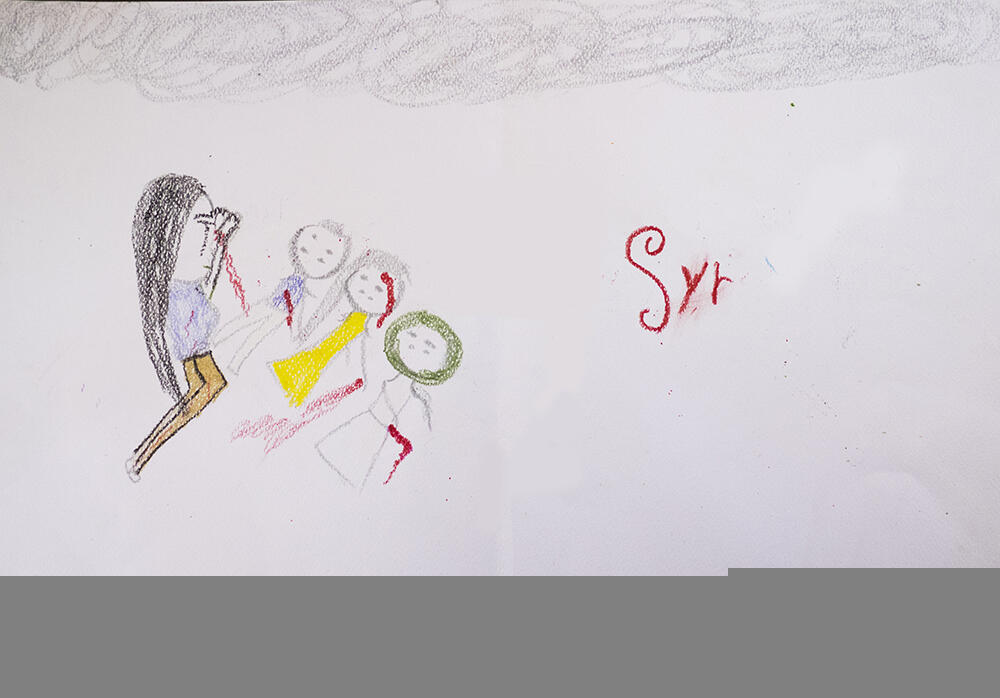

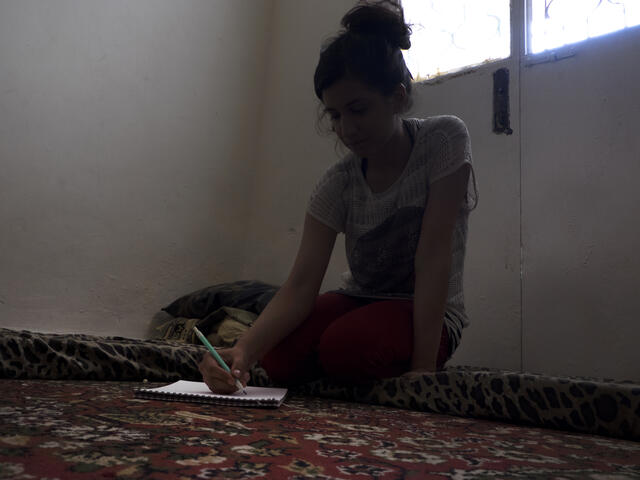

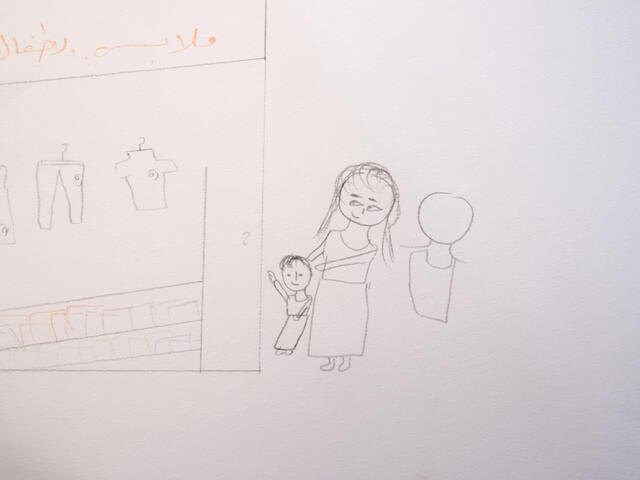

I started drawing and joining in activities like Zumba and theater [workshops] to help me forget about my misery. I don’t like sitting alone without anything to do because everything comes back to me … it’s hard for me.

When I feel pressured, I don’t reveal my sadness or take out my anger at people; I let it out by drawing. I take a pencil and paper and let out everything I have inside. When I finish my drawings, I look at them and see memories. And I think—is this how I was? I should go back to the way I used to be.

But I felt like my mental state was better at the IRC, because I had my friends around me and we would play and joke around.

My uncle and grandmother would visit us at the reception area. I was so happy to see someone related to me—it kept me hopeful. There are still people in this world that I love.

The reunion

After three months at the reception area, we were able to stay with our grandparents. They told us that we would be moving to Amman, a nicer place. I had mixed feelings; I was both happy and sad.

The first two days in Amman, I felt uncomfortable. I missed my friends at the reception area, and I started thinking again. I kept thinking that I would never see my mother’s grave again.

Sometimes my brothers and I get bored, so we start fighting. I don’t like that. I don’t want us to be a source of noise in the house. I keep telling my brothers that everything can be solved peacefully but, you know, they’re boys, they want to show their muscles.

My grandparents are extremely good to us; they pamper us. They have enrolled us in school— we started in September! My wish is to finish high school and get my bachelor’s degree and work as a nurse.

In Syria, I spent two months shadowing nurses. It actually made me a stronger person when I saw dead people on the street—without heads, legs, arms or insides.

I am relieved because my brothers and I are safe, but I miss my family. We left behind so many memories; we left behind a life and our country. The hardest thing to lose is one’s parents and country, and we lost them all.

But I have my dreams. There’s still hope for me to live a good life with an education. My wish is for my mother and father to be proud of me.

*Names were changed for privacy reasons

The IRC’s child protection team works in partnership with the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) and the U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF).