The second largest Ebola outbreak in history is raging in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a country that has faced decades of violence and instability. Over nine months in, the outbreak has infected more than 2,000 people and taken more than 1,300 lives.

This Ebola outbreak is the tenth Congo has faced, but this time Ebola has hit areas where ongoing violence is affecting responders’ ability to control the disease.

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) has been leading infection prevention and control, working in more than 50 local health clinics and training local health workers. Yet case numbers are rising and the outbreak is not yet under control. Recent attacks on health centres have exacerbated the crisis, halting lifesaving aid and hampering efforts to stop this outbreak.

The Ebola response needs to earn the trust of local people and save lives.

This is what it takes to fight Ebola in Congo according to the IRC’s Ebola response team:

1. Focusing on infection prevention and control

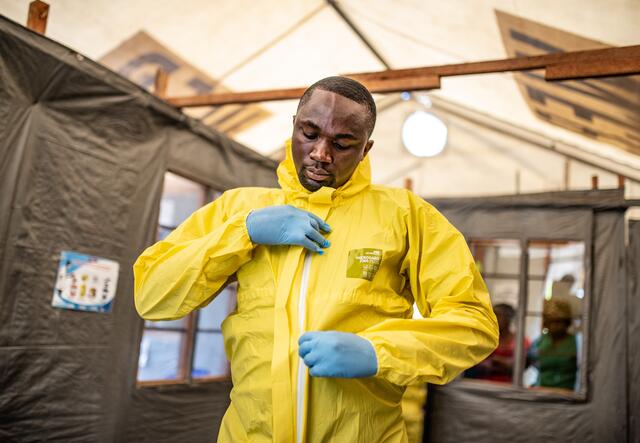

The IRC set up triages in health centres and hospitals across the outbreak areas to screen all incoming patients for symptoms of Ebola. If their symptoms indicate the presence of Ebola, they need to be isolated in a separate room and treated by nurses wearing protective equipment. They can then be transferred to an Ebola treatment centre for further care. All other patients who don’t fit the criteria will remain at the hospital or health centre to be treated for their illness.

We also make sure that the hospital is cleaned with chlorine and that waste — especially from the isolation rooms — is disposed of properly. To that end, we build waste management areas and hand washing stations with chlorinated water in the health centres.

2. Putting your own life at risk

You’re really putting your own life at risk when working with Ebola patients. If something goes wrong, you could die. You can’t go into the isolation room and have had a bad night, not be careful, or not be methodical. You need to be very precise in your work. Perfectionism is required.

On top of that, we have been dealing with direct attacks on health workers. Three of the IRC’s triages in Butembo were burned down in April and May. Our staff luckily weren’t directly affected but they could have been, and they know that. That’s a huge amount of stress to deal with that goes well beyond any sort of normal, everyday work.

3. Increasing engagement with the community

Many patients can be cautious and reticent when they find out they’re being screened for Ebola because of fear of the unknown and a process that can be intimidating. That’s why it’s important to engage with the patients, comfort them, and address their fears while providing care.

There was one case where a woman had had both her children die of Ebola. She started having symptoms and was very likely Ebola positive. The rest of her family had been vaccinated, including her husband, but she refused to be vaccinated. It’s likely she was very afraid. When she arrived at the health centre, we had to convince her to be tested. She didn’t want to go to the Ebola treatment centre so we tested her in the triage, and she tested positive for Ebola. She eventually agreed to go to the treatment centre, but she didn’t want to get in an ambulance; she wanted her husband to drive her on his motorbike.

After receiving treatment, the woman recovered from Ebola and was able to go home to her husband. She ultimately did the right thing but we had to be flexible and work with a conduit like her husband to help. That’s why community engagement needs to be at the heart of the response. It needs to be the core message.

Why we need to keep working to stop Ebola

The number of Ebola cases is spiking and seems to be increasing on a weekly basis, both because the outbreak itself has not yet been controlled and because of the insecurity that makes work increasingly difficult.

Women and children are particularly at risk during this outbreak. In fact, women make up 55 percent of Ebola cases. They are commonly caregivers of the sick, so they are most at risk of contracting the virus. Access to health care has also been historically difficult for women, as they are vulnerable to violence and exploitation.

Many children have been orphaned after parents and guardians succumbed to the virus. Being transferred to an Ebola treatment centre is also extremely harrowing for children, and we see a high level of trauma among children when they are impacted.

The curve of an Ebola crisis can skyrocket very quickly. Each infected case can lead to several other cases, contributing to exponential growth if things go wrong. We need to be acutely aware that we are at a dangerous point in the outbreak and if the response doesn’t change, we could be looking at a very bad situation quite soon.

What the IRC is doing to help

The IRC works in more than 50 health clinics in outbreak areas and trains health workers in their own communities. While some of this work has been interrupted in the Butembo area due to attacks, we continue to provide support to triage posts and deliver vital supplies, including kits to keep health workers safe. The IRC also continues to work in Beni and Goma, including providing specialized support to women and children who have been impacted by the outbreak. Read more about the IRC's Ebola response and our other work in the Democratic Republic of Congo.